The Normal Distribution of People

The Uniqueness Gradient

Hey friends,

Quick plug on two things:

- Podcast: Tune in to listen to this 6-minute episode on Spotify, Google, Apple, or the website, about ‘building a rocketship’, where Ali talks about his thoughts on being a child again, after having completed a LEGO set.

- If you haven’t already, consider subscribing to Daily Insights, a super-short version of this newsletter.

Onward…

I decided to do something different this week, and so, it took a while. This post is one of those long ones, where I have tried to go deeper into a topic I’ve been thinking about: The Normal Distribution of People.

I found this idea interesting because I was thinking about “skills”, “goals”, “greatness”, and about other cousins of ‘self-improvement’. So, this was a rather organic realization to me, and I thought I’ll cut to the chase by sharing my thoughts on this. No stories, no fluff, let’s get to it.

(Hope you like it. Feel free to let me know your thoughts.)

The Normal Distribution of People

Introduction

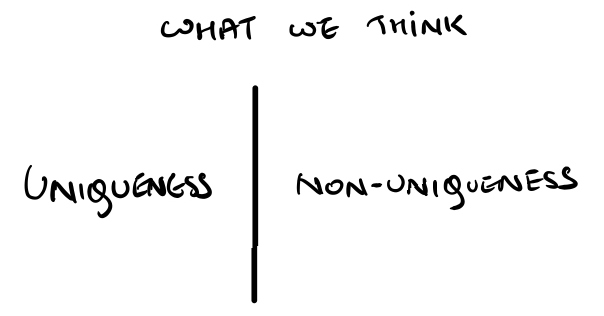

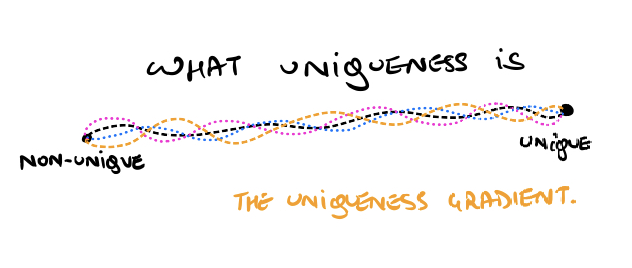

The word ‘unique’ comes from the Latin words unus and unicus, and it means, “being the only one of its kind”, or “unlike anything else”. Going strictly by this definition, I will dig deeper into why uniqueness is not a binary thing, why no one is truly unique, why all people can be plotted onto a normal distribution, and what to do about this whole situation.

You think you are 'unique', because, well, there's nobody else like you, right? This is true. But the whole idea of 'uniqueness' is not a black-or-white thing... I’d say it's a gradient. Sure, you're unique at one level, but on another level, chances are, uniqueness is a common phenomenon.

The Normal Distribution

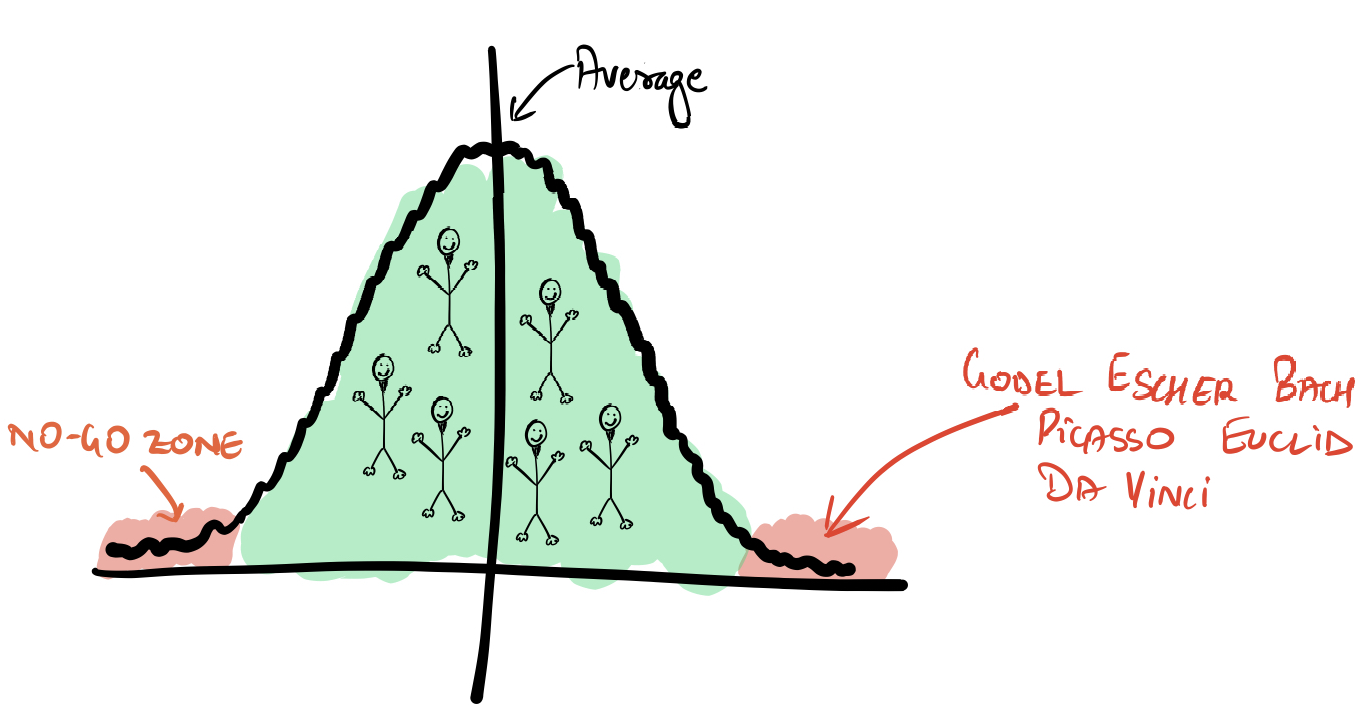

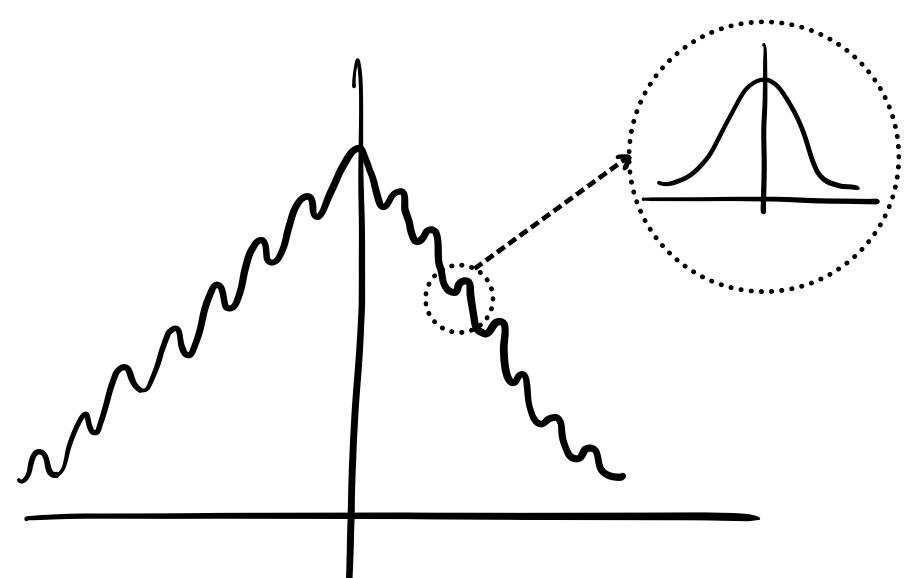

Now, this is a normal distribution.

If you don’t know what this is, please continue reading. If you do know, please skip this paragraph. So, the x-axis shows different values, and the y-axis shows the count of each value. Naturally, the tip of this graph shows that, the value on the x-axis has the maximum count. For example, you can plot the heights of all people here. On the x-axis, you'll have heights of people from 3 feet to 10 feet. If the graph's tip is at 5 feet 7 inches, you can say that, most people are 5 feet 7inches tall.

All people are on this graph

So, now that you know what a normal distribution is, my hypothesis is that, all people can be plotted on the ‘normal distribution of uniqueness’. Sure, if you’re like Musk or Jobs or any of the other geniuses, you’ll be at one end. And if you’re just a bad person, you’ll be on the other end (the “No-Go Zone”).

But if you’re reading this newsletter, you’re most likely going to be somewhere on the graph, not in the extremes. To verify this hypothesis, I’d say 10:1, that chances are, you know people like you, people who’re “better” than you, and people who’re not as “good” as you, at your craft. If this is true, it’s a good proxy to find your spot on the graph.

Impostor Syndrome

Now, some may say this is impostor syndrome, and I’d agree with them. It is impostor syndrome, because, as Seth Godin writes:

“The odds that a pure meritocracy chose you and you alone to inhabit your spot on the ladder is worthy of Dunning-Kruger status. You've been getting lucky breaks for a long time. We all have.”

If you look back to your days when you were a kid — unless you had composed some god-level song by 12, like Beethoven — you’re likely to not have found your 'true calling until age 18 or 20. But by that time, it’s late to become a Da Vinci or Jobs.

Also, chances are that if you’ve not found your “calling” or whatever they call it, by 20, the idea that you were the chosen one for XYZ is deeply flawed.

The Nicety of Your Position

Two things, before we go forward:

- It’s not a “bad” thing if you’re not in the GEB domain, and

- You can be super smart, but that still doesn’t put you in the GEB domain.

Start with the first thing. Popular culture, media, and the Silicon Valley rhetoric makes us believe that unless you’re inventing another planet altogether or unless you’re solving big “important” problems, you’re mediocre. In other words, a good proxy for your greatness is your ‘impact.’ Of course, I’m oversimplifying here, but that’s what it usually boils down to — Either you’re a Musk or you’re not (and if you’re not, that’s bad).

There’s a slight qualification here, though.

Your ‘greatness’ is 65% a function of your context, and 35% a function of your skills. Let’s dig deeper into this. In this Atlantic article, you’ll read how meritocracy harms everyone, and specifically, their inner being. There’s other stuff about inequality in the article, but one key point is that privilege begets privilege and that the “elite” resist any change that harms their position of eliteness.

As people on the planet increases, as competition increases, resistance for you to get into the GEB domain increases as well. Of course, this is a hypothesis, but the more I think about the past (and why great folks achieved lasting ‘greatness’ in the past), the more this seems to be true.

Yes, of course, there will always be exceptions, like the Nobel Prize winners or the richest folks on the planet. But exceptions prove the rule, that, reaching the GEB domain is harder today, than before. My point is, that’s okay.

Which brings me to the second idea: You can be super smart, but that still doesn’t put you in the GEB domain. You’re either born a genius, or you’re simply not. Yes, you can acquire greatness to an extent, but that still doesn’t (and will never) put you in the GEB domain.

Again, that’s okay. It’s just a matter of recognizing one’s own limitations, one’s own inadequacies, and one’s own challenges. The more you’re self-aware, the more you will work to improving on the things that matter to you. That’s, really, one of the main points of this essay.

I’ve written about becoming a ‘multipotentialite’ and being a ‘pracademic’ before, and both these ideas align with the fact, that, if you haven’t found your calling by age 20, it’s almost certain you won’t be in the GEB domain. Yet, you can asymptotically strive to get there, by pushing rightward and recognizing your existing limitations.

The Embedded Normal Distribution

For the sake of argument, let’s assume you have acquired greatness. You are far into the right, to the point that you have pushed the bubble of human knowledge. But even then, your position on the right side of the normal distribution of people is dependent on two things:

- Time, and

- Fractal

Let’s dig deeper. In 5 billion years, the Sun will run out of oxygen and we will all die. I’d say, we may even die before that. Now, in that huge timeframe, chances are, someone will completely wipe out your legacy. Of course, this shouldn’t demotivate you to do what you’re doing. In fact, if at all, it should motivate you even more. See this video:

But the meta point to understand is that, on a large enough time scale, your position in the GEB domain is, by nature, temporary.

The second point to understand is this:

If you look at this graph close enough, see how I’ve drawn the normal distribution of people. Every hump is, in itself, another normal distribution. Meaning, even if you’re on the far right of this graph, there will still be others around you. You can never be the single most-unique person, or the single, “greatest” person.

So, What Next?

This understanding is liberating. That you are, inherently, non-unique, and that you will never be truly unique, is gratifying, fulfilling, humbling. Embrace it. Do what you’re doing. Excel at it regardless. That’s what matters, not the heavy burden of wanting to be unique.

See you next time,

Abhinav