The Infinity Gauntlet of Media

The Internet is like 'Infinity Gauntlet'. In it, the Internet's "Infinity Stones" have — instead of bending rules — created new rules altogether of how we interact with media. A few examples:

- TikTok takes the world by storm,

- Clubhouse (read 'Sriram and Aarthi') hooks everybody to audio,

- A Reddit forum takes down the Street,

- Substack (and Onlyfans and Patreon) empowers creators, and

- Dispo (a simple photo app) commanded an incredibly high valuation.

So, in this essay, I want to go through the powers of Media's Infinity Stones and make sense of how we got here, where we are, and where we are going.

Chapter 1: The Pre-Internet Media

This is the Time Stone.

You can't understand the future without understanding the past; and you can't understand media without understanding how technology works. After all, media is a result of technology, and how we communicate is a function of available tools.

To understand media, then, is to understand technology.

So, to wrap our minds around the evolution of technology, divide time into four buckets:

- Pre-1400s: The Pre-Industrial Age

- 1400s - 1930: The Industrial Age

- 1930 - 1980s: The Electronic Age

- 1980s - To Date: The Information age

Pre 1400s

Start with the pre-1400s. Imagine, for a second, that the act of writing does not exist. Imagine that you don't know how to write. Or, imagine that the act of writing is unimportant. People were precisely like that until the 4th century, when Sumerians (possibly) invented writing. Until the 4th century, writing was an act reserved for codifying law, ethics, or socially-acceptable practices. The Sumerians are likely to have developed the purpose of writing as a tool to disseminate information.

The Industrial Age

But you couldn't have disseminated information by writing 1000 books by yourself. You needed some (mechanical) way to help you scale that dissemination, and do it repeatedly. This is what printing provided, in part, at least. 'Block printing' — as invented by the Chinese in 6th century — helped in reaching scale, but not to a point where it was meaningful enough. In the 11th century, the Chinese invented some form of movable printing, but that did not scale due to religious considerations. (Arabs did not approve of printing the Qurʾān well until 1825.)

Fast forward thousands of years to the 1400s, when Gutenberg invented the movable type of printing, with metal, ink, paper, press.

This changed everything.

Take books. Suddenly, you didn't have to handwrite books.

Before Gutenberg's invention, books were painstakingly handwritten. Of course, writing and paper had existed for a long time, but printing — at scale — did not, which made the dissemination of information practically infeasible. Besides, the act of writing introduced human errors, biases, and perspectives that shaped our collective knowledge. (No two books were the same.)

The excessive control of scribes, priests, and central authorities over the "message" was a function of the medium, which made it impossible for the masses to have any say over the message. The message — like the currency Yuan — was tightly controlled.

The printing press upended the monopoly on distribution, initially held by the enlightened.

It's hard to overstate the importance of the printing press, which helped usher in massive cultural movements like the European Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. Until then, the Church had controlled the distribution of religious texts — the Bible wasn't widely available.

In essence, this was the first time that technology, and by extension, media, disrupted those who controlled the means of accessing important knowledge, at scale. (This is a constant theme we will see throughout the essay ie how technology enables media to disrupt incumbents, at scale.)

On a tangent: Media is the collective noun, used to reference broadcasting, publishing, and the internet. The commonality in these 3 media is that each is a different form of distribution. So, when I say that 'technology enables media', I mean that tech enables a different means of distributing content. And that is how technology enables media.

As printing scaled and became more mechanized in the 19th century, the jobs of publishing, editing, and creating content, decoupled. Now, a publisher was separate from the author, the author, from the editor, and on and on. The author wasn't supposed to worry about how to publish and the publisher wasn't supposed to worry about what to publish. (Classic comparative advantage in application.)

This comparative advantage and constraint on free-flow of information helped newspapers form a monopoly over information distribution. (I won't go into the specifics of newspapers here.)

The Electronic Age

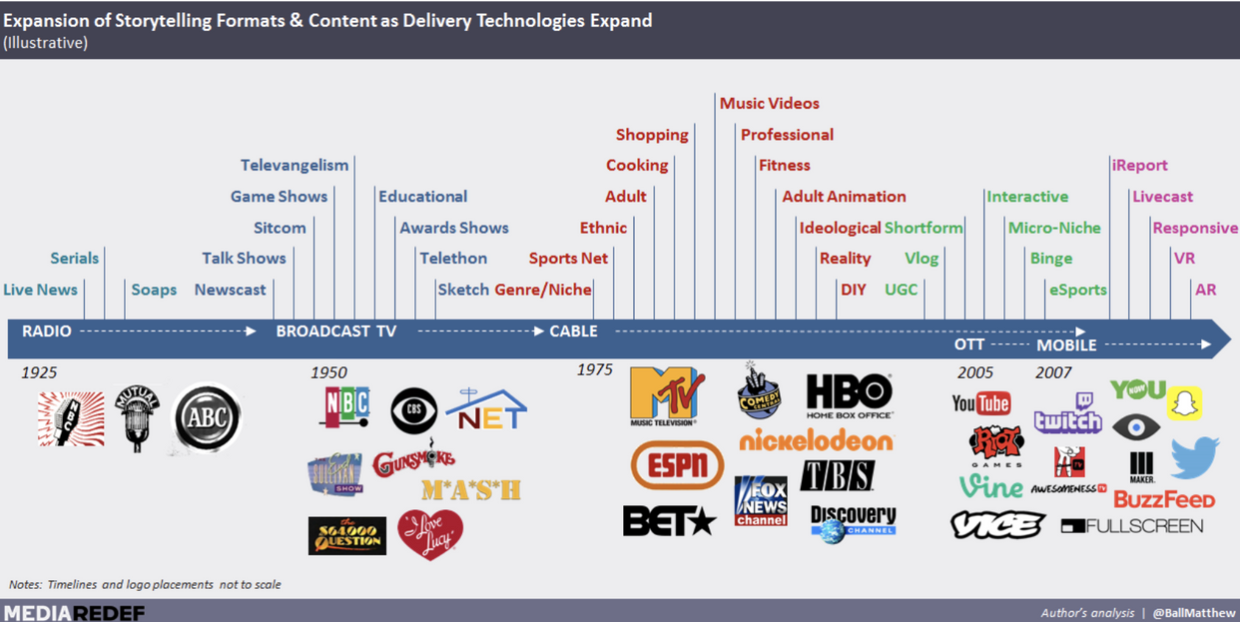

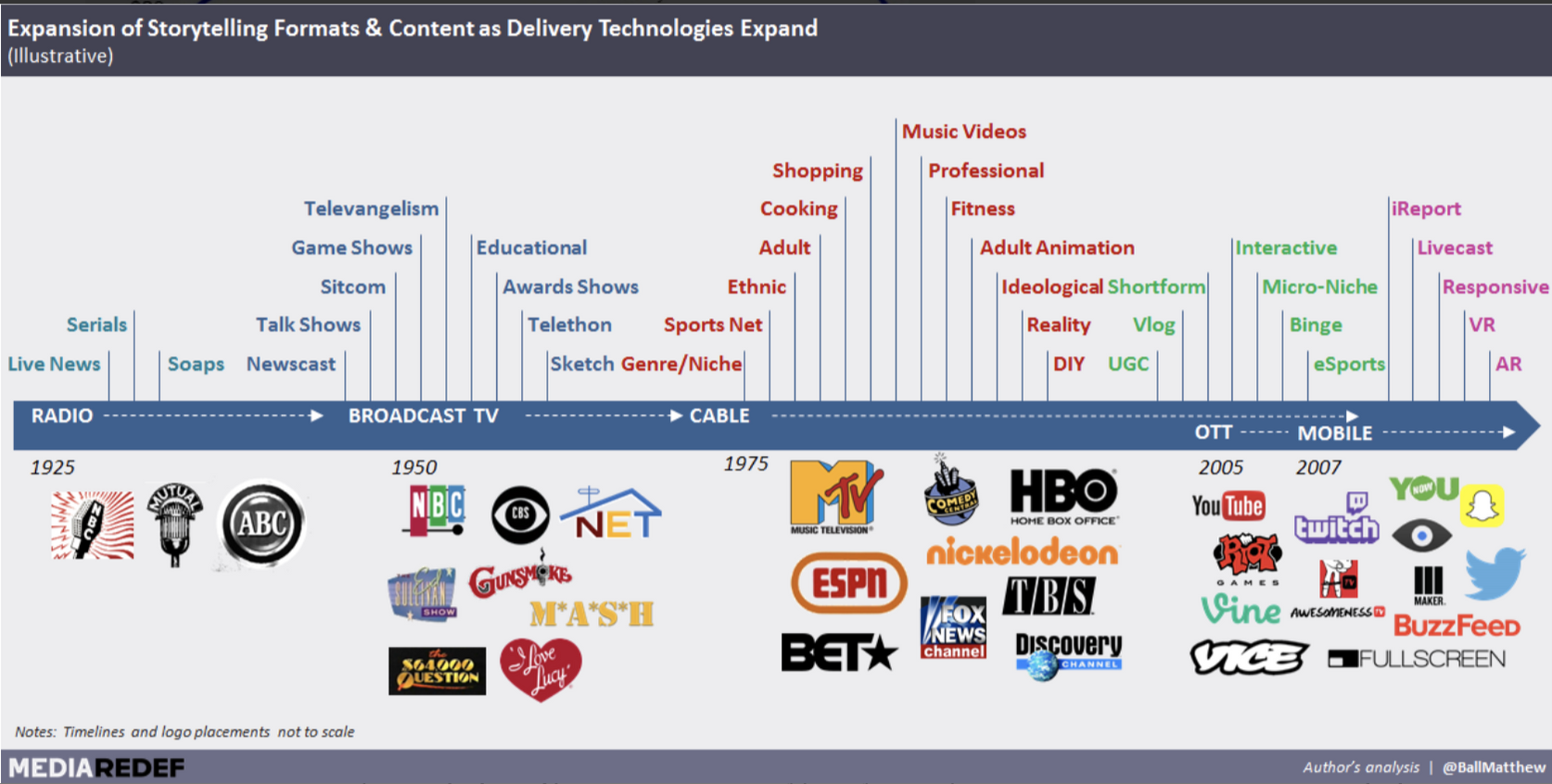

Fast forward to the 20th century, and with the newspaper as the primary medium, other forms of media emerged. Radio started in 1920, with live news being reported first. The radio station '8MK' reported election results; following suit, other radio stations reported news events and 'radio dramas' like A Comedy Of Danger and War of the Worlds. (You can listen to a few radio broadcasts below.)

The radio era continued for many years. From 1928 to 1935, many companies started making TV sets and TV stations, which gave rise to broadcast TV. Initially, the Federal Radio Commission was only able to broadcast silent images with their radio programming. Soon enough, though, the company GE's television division, WGY, **successfully transmitted the first-ever TV show, called The Queen's Messenger. (See the press release here.) WGY even managed to broadcast the show from Schenectady to Los Angeles. Here's an excerpt from the show.

Here's the press release:

Later, in 1930, the British PM, Ramsay MacDonald, and his family watched the broadcast of the drama The Man with the Flower in His Mouth.

Initially, TV was a privilege, reserved for the rich or powerful. Soon, though, more people began got access to broadcast TV. And the first-ever widely available TV broadcast was the newscast of Today, on Jan 14, 1952. Have a look:

In case you were curious how broadcast TV works, here's a 2 minute video and below is a longer, 10-minute video:

As broadcast TV evolved, 'cable TV' was also starting out. Cable was better not only because physical transmission of content (via the cable) was more reliable and had better bandwidth, but also because it allowed viewers to watch multiple shows, and not be restricted to one broadcast. As far as I know, this was the first example of bundling different cable providers' TV programs.

Content exploded.

From just news to talk shows, we moved to niches, cooking, music videos, anime, non-fiction, and other interesting creative genres. This was the age of HBO, Nickelodeon, Discovery, MTV, and Fox News.

The TV craze was only settling in as the Internet was taking off. By the 1970s, ARPANET was growing fast, starting from 15 nodes to 200 nodes. By the 1990s, the Tim Berners Lee had invented the world-wide-web, which suddenly supported the massive commercialization and mass availability of the Internet.

The Information Age

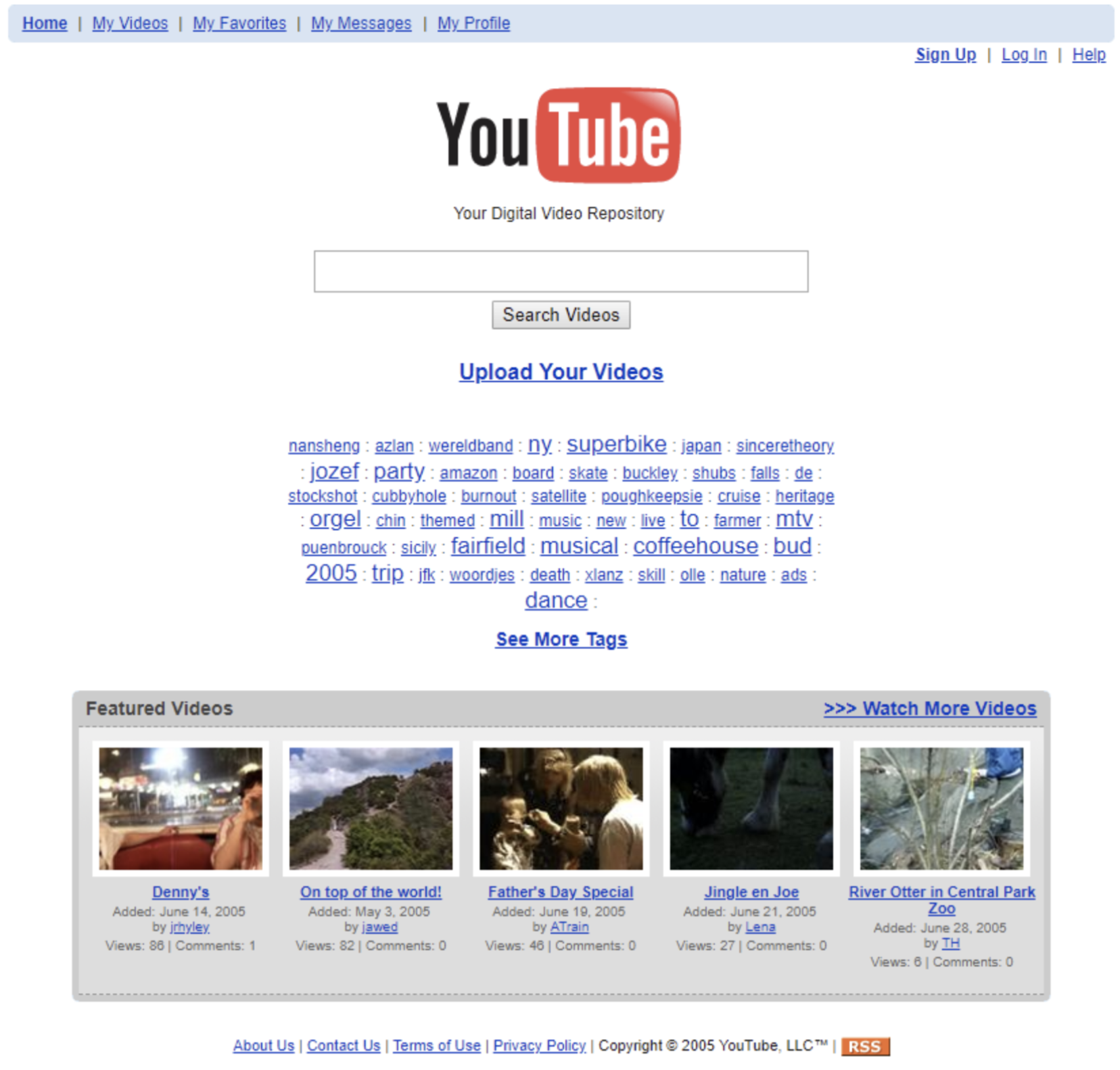

With the exploding usage internationally, the Internet was catching pace and snowballing into something larger. By 2005, we had the ability to stream videos directly over the Internet: YouTube had entered the game.

That videos could now be streamed directly from the Internet was a big moment in technology's evolution. No longer did you require a broadcasting station; no longer were you impacted by the bandwidth limitations of cable TV; no longer did you require a satellite and a set-top box to watch a video. Of course, YouTube still had a long way to go — bandwidth was poor and we had Jawed Karim talking of elephants' long trunks.

But the platform witnessed success soon enough, when Nike dropped a video of Ronaldinho getting his boots. This video amassed 1 million views and validated the potential of video. Sequoia jumped in with $3.5 million in November of 2005, investing another $8 million in 2006 with Artis Capital. Google bought the platform a year later, calling it "the next step in the evolution of the Internet."

On a tangent, you can have a look at the evolution of YouTube, Netflix, Google, and other websites here.

This was the beginning of the information age.

The Internet had disintermediated the distribution of information once again, effectively overriding 'limited shelf space' of CDs and physical stores. (Netflix was still offering DVD rentals for a monthly price.)

In an article in The Guardian, Tim Wu describes the information age. From the article:

The attention merchant’s basic modus operandi: “draw attention with apparently free stuff and then resell it”, a business model that is still alive and prospering on the contemporary internet.

Chapter 2: The Internet's Impact

The Internet drove a wedge through the sanctum sanctorum of analog media: distribution.

The Time Stone was one part of the story. The Power Stone is another altogether. The Internet was the 'time + power' stone, and it wiped out the linchpin of pre-Internet media, 'distribution'. Think of it as a castle's moat being obliterated by F16s. (Neither will F16s spare the moat nor the castle.)

As Balaji said:

... Once we are equal on distribution, then we can actually speak to each other as peers. And it’s futile to try to argue with someone who has way more distribution and is hostile, you just need to build your own distribution, which is much more possible in the internet age.

So the Internet changed the basic rules of the game, without changing the game itself. Pre-Internet media monetized information by distribution; newspapers sold their captive readers; radio and TV sold their inventory. The Internet multiplied inventory (cost of an additional webpage was zero), quantified metrics (as it coupled ads with performance), and made captive audiences accessible to all.

As the Internet scaled from ARPANet to an international infrastructure, news content became a commodity, speed became a necessity, ads became the norm. In doing so, the Internet drove up competition for every radio, TV, and newspaper company. It took away the most valuable consumers; it took away the youngest ones as well; it changed the economics of the business model.

And let's not talk about book shops, music shops, DVDs, or CDs; that we find these technologies 'archaic' now, only shows the deep impact that the Internet has made.

Coupled with smartphones, tablets, laptops, and broadband speeds, Internet has encouraged consumers to switch from analog media to Internet media.

The Internet's impacts seem tangible, but they're beyond just redefining the medium. More than distribution, the Internet changed time as we understand it.

Chronos became Kairos.

In Greek mythology, there are two words for time: chronos and kairos. While the former refers to linear time, the latter refers to the opportune moment. To understand the Internet's impact, then, you have to understand how kairos interrupted chronos.

That you can binge watch Netflix, use Discord endlessly, go to Clubhouse and find jobs, or listen to Olivia Rodrigo and The Beatles one after the other, shows how the Internet has created "multitemporality", the superimposition of time, on itself.

This means you don't need to wait to do one thing after another; you can bypass time to do things indefinitely (of course, until you quit or die.) The point is that the Internet has changed how time itself works, and that has percolated into the media we consume.

In essence, as VGR puts it, we've moved from 'schedule-based time', to 'on-demand time', from no (or delayed) gratification, to instant gratification. That you can do 10 things simultaneously allows you to bypass traditional temporal constraints, and move to 'multitemporality', ie when time is multiplied.

Now, no longer do you need to wait for a TV show to be broadcasted at a particular time, and adjust your life around it; you can just stream it...

No longer do you need to physically go into a CD shop and buy a CD; you can just stream music...

No longer do you have to dream about talking to celebrities; you can just tweet at Elon Musk and he'll (probably) reply.

I’m an alien

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) February 12, 2021

The second impact of the Internet was allowing rapid asynchronicity. No longer did you have to wait for a letter to be delivered, or wait at the phone line until the recipient picked up. You could just text or email, or better, connect over VoIP. Of course, this is mundane for us now, but to understand how far we've come in a short time period, it's important to take note of this mundanity. Radio and TV were temporally programmed. After all, you only had 24 hours in a day. But with YouTube first and now OTT, the Internet blew out this temporality and gave rise to rapid asynchronicity.

Finally, the Internet gave rise to abundance of everything. The biggest constraint was not time, not content, not entertainment anymore — it was simply your appetite to consume. (Netflix spent ~$17 billion last year to create content)

Notice how, as media evolves, our relationship with time and our behavior changes.

As we talk about the Internet's impact, I also find it useful to particularly look at how it has impacted the analog newspaper industry at large.

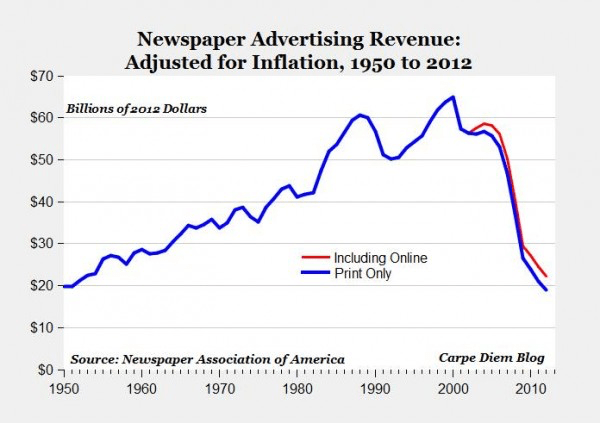

In his article here, Ben Thompson talks about how newspaper ad revenue has declined over the years. This graph is telling of what disruption really does to a sustainable business model.

I like to look at the above chart as only one predictable consequence of the evolution of media. See timeline chart below, showing how distribution has evolved over the years.

From 1880 to 1910, newspapers gained ascendancy; they were, arbiters of information. Newspapers per household were more than 1. Post World War II, though, newspapers declined in three key stages:

- From 1.4 per household in 1949, to

- 0.8 per household in 1980, to

- 0.4 per household in 2010.

Also, the iPhone had only launched in 2007; the mobile phone market was picking up pace; from 2010 to 2020, mobile exploded, and with it, the availability of content, news, entertainment, what have you, increased as well. Newspapers, though, still carried the same amount of content — you were physically restricted to broadsheet, tabloid, or other formats. (This is where scale and distribution meet again.)

The Internet's scale with its rapid distribution capabilities made things difficult for analog media.

Rewinding a bit, three key points:

- Internet divided time.

- Internet replicated time.

- With its ability to distribute things fast, Internet had multiplicative impacts on media. This impacted analog media.

As the Internet moved things online, it made the production of a physical newspaper difficult. No longer did you need to cut trees, import newsprint, and use ink or plates to process yesterday's news. Now, you could produce the same news in a second, without additional cost.

So, the Internet turned on its head, the 'production game' that newspapers played. It played a different game altogether: the game of attention. But as it bypassed practical constraints of time through multitemporality, it soon found a new constraint: attention.

Time is infinite, attention is finite.

To monetize attention, then, the natural response for online players was to leverage Internet's unlimited inventory and offer everything to you: food, movies, songs, arts, medicine, stuff, furniture, houses, cars. In contrast, it's practically infeasible for newspapers to give you this entire multimedia experience. We've talked of the physical constraints above, already.

To quote Balaji again:

Just like Google News in 2002, put every single newspaper in competition with every other one. And then all of these local newspapers shuttered, and only the really big national distributors became international centers, ones that could respond to it. And then the smart ones actually saw that. And then you had new things come up, like pure digital outlets.

That said, there are still places where the newspaper industry is flat, meaning, people are not discontinuing to read the paper. It could be a habitual thing, but the long and short of it is that newspapers still have a value proposition that the Internet does not match up to.

That value proposition is 'status'. A physical newspaper gives you status, heritage, prestige, things that performance-based advertising of the Internet just cannot. Take TV; that the CPM for a Superbowl ad is $50 is telling of what offline, analog media can still offer that the Internet cannot replace: status.

In all, there are things the Power Stone offers: scale, distribution, multitemporality, asynchronicity, and abundance. But there are things it cannot offer as well: prestige, heritage, status.

Chapter 3: The Great Bundle

<aside> 💡 To recap, so far, the above chapters have painted an interesting picture about what happened. We've understood pre-Internet media, we've seen how Internet changed media's landscape, and we've noted key differences between online and offline mediums. Now, we'll go one step forward to understand how Internet media works today.

</aside>

In addition to being the time and power stones, the Internet is also the "Reality Stone". Its reality is that it's a 'Great Bundle'(and we love bundles.) Everything the Internet offers is, quite literally, a datagram in a packet-switched network, in other words, everything is a bundle. This includes the text you're reading now, IG photos you scroll through at lunch, YouTube's videos you watch at midnight, and of course, Netflix, and Clubhouse.

It's all a bundle.

You derive meaning from the Internet because of the bundle, which allows you to switch from X to Y to Z, in an instant. Now, imagine the contrary. What if you could only use one app at a time without being able to rapidly switch from doomscrolling Facebook to reading The Atlantic to playing 'League of Legends'? Chances are, you'd dislike the Internet very much then.

Which means that the whole point of why we like the Internet is because of the bundle first, more than the plain convenience it offers. The bundle gives us the ability to do anything, anytime. And that's why we love bundles.

Jim Barksdale once said: There are only two ways to make money in business: One is to bundle; the other is unbundle.

Naturally, then, to succeed on Internet, each company should also be a 'bundle' of sorts. Google is a bundle, the iPhone is a bundle, your social network is a bundle, your shopping cart is a bundle, your streaming service is a bundle. Everything you see around you is, in some way, a bundle, and in some way, an "unbundle" as well.

Internet companies generate value when they have the characteristics of what makes the Internet tick, ie when they are 'bundle companies' themselves.

So it doesn't matter whether the bundle makes sense economically or not. The economics will follow, as Chris Dixon put it very well here. (I also wrote more about bundle economics here.) The basic point is that every company needs to have a bundle, or better, be one.

Come back to media now.

Take Disney. Disney's "platform storytelling" effectively offers 'Disney as a service' (or better, a 'bundle'). The company works because it's one company singly focused on cross-promoting its IP, thereby offering a bundled, multimedia experience to the consumer. Its revenue validates this notion even further. That it earns 34% of its revenue from theme parks, 13% from movies, and the rest from interactive games and consumer products only shows how Disney is a 'bundle company', not just a 'media company'.

Disney is one example of how media companies today have moved from offering 'media services' to offering 'bundled experiences'.

Take Apple's foray into 'The Great Bundle', which, because Apple owns the hardware, makes Apple incredibly successful at offering bundled experiences. For example, AppleTV+, AppleMusic, AppleArcade, and AppleFitness+, all being offered in 'AppleOne'. Apple understands that a pure hardware-play is not as scaleable as a subscription-based, bundled offering, and so, Apple, too, is a bundle company, offering bundled multimedia experiences, not services.

The point being that, media companies are now bundled-experience-offerings, which is a pretty big shift into how industry is responding to the Internet at large.

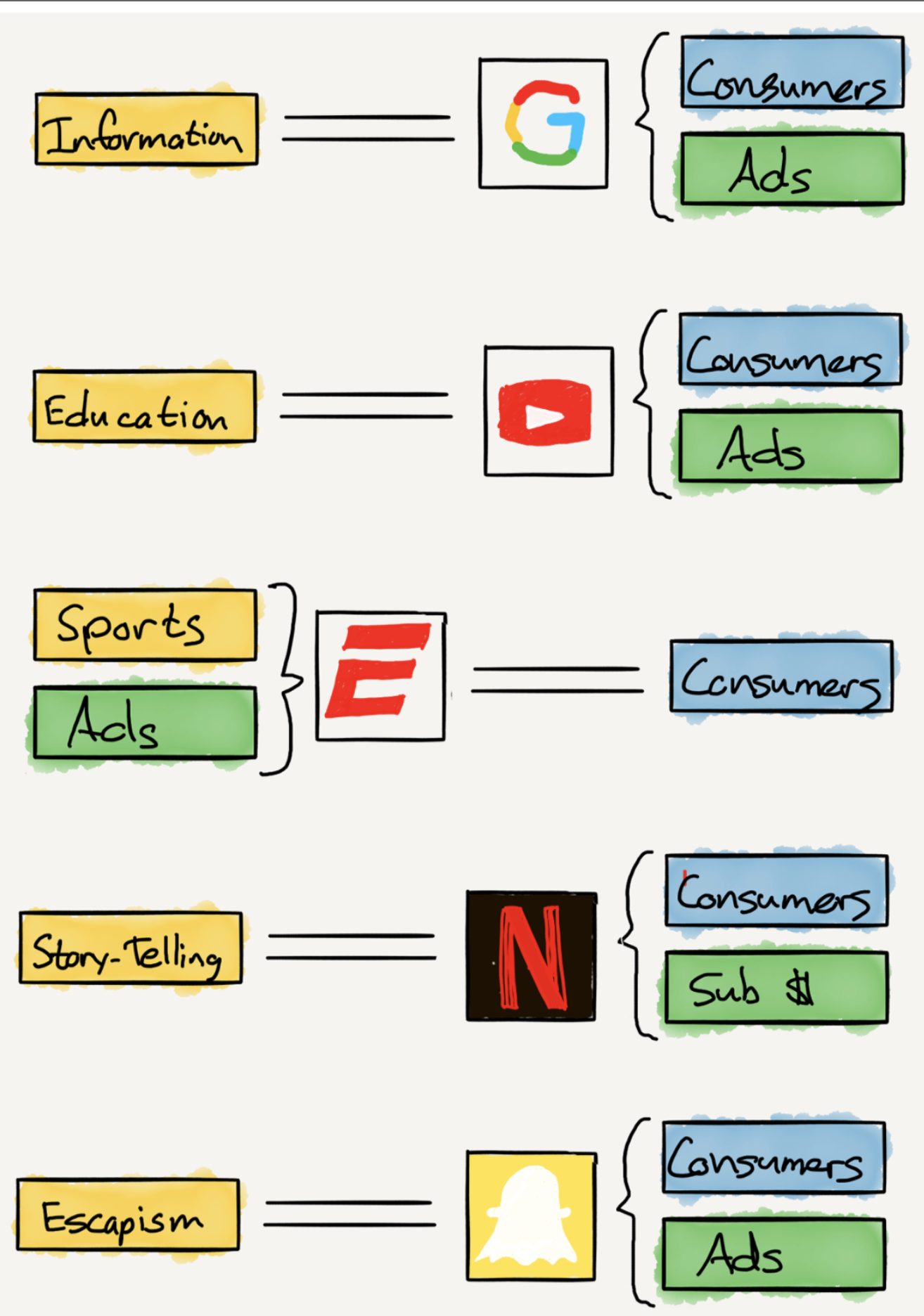

I won't explore Google or Facebook or Amazon or Netflix, because it's pretty self-explanatory to see how they're bundles, and Ben Thompson's picture (below) does a good-enough job to explain it.

Then, there are services which are not bundles and yet incredibly successful as well. Companies that do one thing very well. DoorDash is one example that delivers food, period. These are the unbundled companies, offering specific services and doing it so well that they outshine others.

As Balaji has also said:

... it’s also true, you think about you unbundle all the songs from all the albums then you’ve rebundled them in Spotify playlists. You unbundle every single article, and website, and URL in the world and you rebundle them into a Twitter feed.

So, all this is to say that, the Internet has helped scale the quantity and quality of news, information, and media we consume, effectively also forcing companies to become "bundle companies".

Chapter 4: The Rise of The Creator

Finally, there's the "mind stone", which is a proxy to emphasize the "rise of the creator". (There are two more stones left but the analogy breaks down if I extend it further.)

Traditionally, legacy media companies and established publishers controlled what content gets out into the market. Roll back to Chapter 1 and you'll see how this happened, primarily because distribution was controlled by publishers.

With Internet, the rules of the game changed completely. The Internet decoupled "distributors" from "publishers", making distribution so easy that any aspiring creator need only focus on publishing.

In essence, the Internet transformed every single person on the planet into a media company. Take social media, for instance, which made advertising and 'access to the end-consumer' so frictionless for all that every small creator or business could now become a part-time content-creator, effectively helping scale their original strategy.

And while social media gave birth to the OG creator economy, auxiliary creator tools have made life 10x easier. You can now record and edit videos or podcasts, collaborate on editing videos, host podcasts, publish videos, have a financial studio, "presubscribe" to things, pay creators on Twitter, and do a 100 other things, at the same time. (See chapter 3).

That there exist TikTok millionaires, rich YouTubers, and even incredibly famous IG influencers only shows how the Internet has democratized the ability to publish content, become a creator, and more importantly, transform oneself into a "niche media celebrity", with your own niche following. In particular, let's look at a few media platforms that have fueled this trend:

Patreonallows creators to go beyond ads, toward fans, and monetize fans via membership and subscription.Gumroad, a commission-based business, enables creators to find audiences, customers, and part-time employers.Substackmakes it incredibly simple for you to start a newsletter and charge your audience for it.Ghost, a paid CMS, enables creators to focus on creating content, while taking care of the "rest".

With such access, we're now seeing how creators are becoming businesses, with content as their product. I particularly liked this tweet of David Perell, that hits the point straight about where we might be headed:

Open questions:

— David Perell (@david_perell) January 24, 2021

1) When will the first creator IPO?

2) How can we normalize the “Chief Evangelist” role at companies so creators get equity in startups?

3) Can creators build generational wealth without managing a big team?

4) What are the leading causes of creator burnout?

So, be it audio, video, text, or visuals, content rules, content monetizes, content wins.

But now that everybody can create content, UGC has also changed the game for creators. Earlier, it was brands vs a few recognized creators. Today, it's brands vs every single creator. TikTok stars, Twitter-stars, YouTubers, Indie artists, Indie teachers... everybody is a creator, and everybody is competing with everybody else, thanks to the Internet. Their ammunition: content; their vehicles: Internet.

One time, as I chatted with my friend, we discussed how Elon Musk is, in fact, also a creator, and how he's silently running an incredibly successful media company on the side. Take these tweets, for instance:

Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) August 7, 2018

It’s inevitable pic.twitter.com/eBKnQm6QyF

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) July 18, 2020

The point being that Elon's 55m+ followers are his own audience, and he can create and erode tangible value (from Bitcoin and from Tesla's own stock) in an instant, all by using his own media asset, himself.

This is to say that the Internet's evolution today has reached a point where, more than content, creators are now emerging out of nowhere. And the best part, you don't even know that some people are fundamentally creators.

Chapter 5: Conclusion

In summary, what do we make of everything?

The point is that, media is what binds us, drives us, programs us. Balaji said it best over here:

If code scripts machines, media scripts human beings, even in ways that we don’t fully appreciate.

Media scripts us.

At a point when we know everything around us due to media's tools, I thought it's important to go a bit deeper into the philosophy of media and understand its origins, how it's changed, and where we are right now. Of course, the above four chapters are only starting points, more like tools (or mental frameworks) you can think about more, to explore any situation.

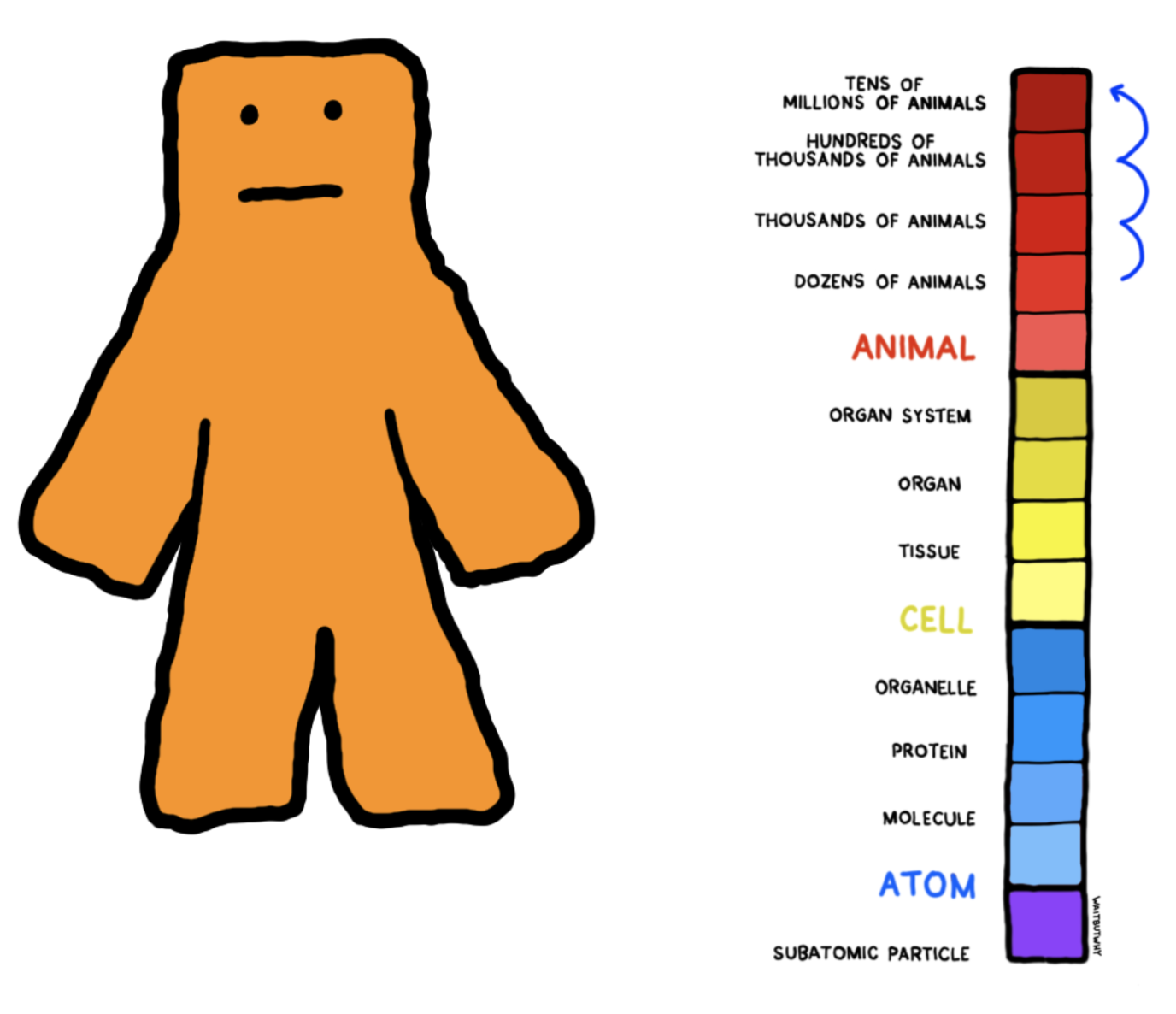

Media is changing, which, in effect, is changing how we behave as a giant (H/T Tim Urban).

And since Socrates said, "Know Yourself", the intent of this essay was to help us understand ourselves, a bit better.

Thanks for reading.